“The diaphragm is the most important muscle we have. There is no if, and, or but about it.”

That’s a bold statement from Brian MacKenzie, author and founder of Shift (formally known as Power Speed Endurance) and the Health and Human Performance Foundation. Bold statements are often met with skepticism in health and wellness, which is why it’s noteworthy when thought leaders from different disciplines agree; the respiratory diaphragm may be the most underappreciated part of human anatomy.

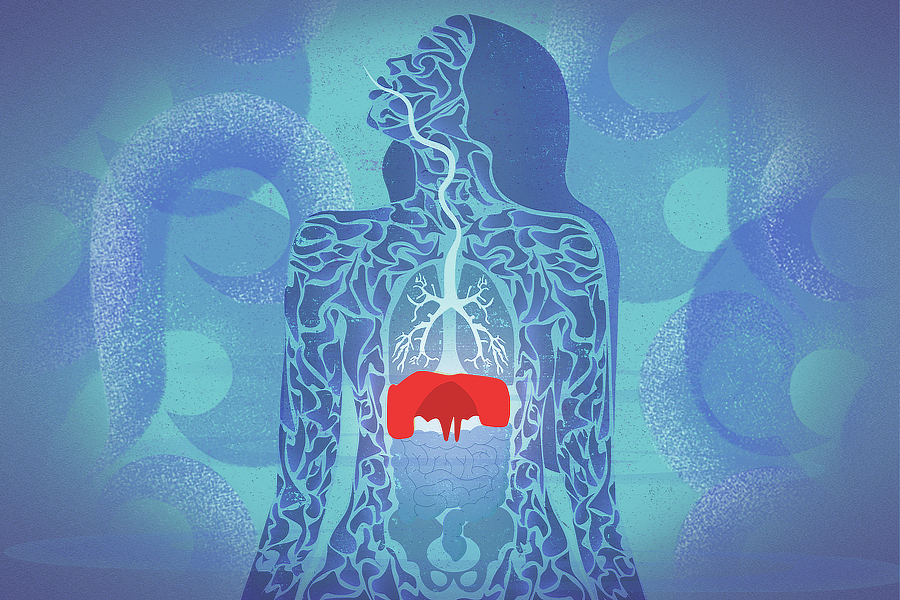

This is something Dr. Belisa Vranich, clinical psychologist and author of Breathe: The Simple, Revolutionary 14-day Program to Improve Your Mental and Physical Health and Breathing for Warriors, sees every day. She works with patients to optimize their mental and physical health with proper breathing techniques at her private practice in New York City. “You ask any educated adult about it, and despite the fact that the diaphragm is this enormous, complicated, and important muscle, they don’t know what it looks like or exactly how it works,” says Dr. Vranich. “The pictures we’ve seen of it are so underwhelming, we don’t really have the impression of how big it is or where it’s positioned in the body. It’s not an auxiliary muscle at all. Our body falls apart without it.”

The diaphragm may be our muscle of respiration, but it’s more than breath. It has an impact on all of our major physiological systems; posture, circulation, immune function, digestion, emotional regulation— the list is long.

As Tune Up Fitness co-founder Jill Miller says, “The diaphragm is an avatar for your entire body.”

Once you learn about the many functions and facets of the respiratory diaphragm, it becomes clear that dysfunctional diaphragmatic breathing has a cascading effect on your physical, mental, and emotional health.

The Respiratory Diaphragm

The word diaphragm is derived from the ancient Greek word diáphragma, which means “partition.” The respiratory diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle that sits in the middle of the trunk, between the chest and abdominal cavities. It has two hemispheres, the left hemidiaphragm and right hemidiaphragm, attaching to the lower six ribs and converging at the top in a central tendon. Each hemidiaphragm has a long tendinous structure, referred to as the right and left crura, that attach to the lumbar spine. During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts, descends, and flattens out, allowing the lungs to expand, fill with air, and deliver oxygen to the body on a cellular level. During exhalation, the diaphragm relaxes and ascends back to its resting dome shape, allowing the lungs to empty and expel carbon dioxide.

Says Dr. Vranich, “When we think of breathing, we think of these little cut-out images of the lungs, and the fact is the lungs don’t do anything on their own. They don’t move, they don’t inhale, they don’t exhale, it’s really the muscles around them that gets them to move. All of these pieces are depending on each other to do the right thing.”

Holly Clemens is a professor of Sports and Exercise Medicine at Cuyahoga Community College in Cleveland, Anatomy Trains teacher, and Yoga Tune Up® instructor. She likes to compare a healthy diaphragm to an umbrella that moves with ease. “As you inhale, you open the diaphragm like an umbrella, expanding the ribs to make more room for the lungs to take in oxygen. When you exhale, just as if you’re lowering the umbrella slowly and carefully, the diaphragm relaxes and recoils, and the carbon dioxide can be breathed out. If you open up the umbrella fast and hard or the mechanism is not working properly, it wears out. The same thing can happen to an inefficient diaphragm. If you load it up too quickly, and keep it in a locked position for a while, it can result in adhesions to the diaphragm from surrounding organs. It can’t operate efficiently and properly. This can impact the overall function and health of that important respiration organ.”

The diaphragm is innervated (stimulated) by the vagus nerve and the phrenic nerve. The phrenic nerve originates in the cervical spine and provides motor control of the diaphragm.1 One way to appreciate how breath is impacted by the phrenic nerve and the diaphragm is to think back to a time you had the “wind knocked out of you.” This is something many of us experience in sports (getting hit in the gut by a ball, for example) or a fall and can’t catch our breath. When this happens, the phrenic nerve has usually been shocked, and the diaphragm is briefly paralyzed.2 While it normally resolves very quickly, the brief moments of gasping for air are illustrative of the power of a functioning diaphragm. The other way the diaphragm makes itself known is through hiccups. Hiccups are involuntary spasms of the diaphragm, and that familiar sound you hear is the sound of your vocal chords snapping shut from the sudden force of air in your throat.

The respiratory diaphragm is also a crossroad for three other critical biological structures, with holes for the following:

- The esophagus, connecting the throat to the stomach

- The vena cava, carrying blood from the lower body to the heart

- The aorta, carrying blood from the heart to the rest of the body

Through this lens, the diaphragm is not a partition— it’s a hub. “People look at the diaphragm and think it’s a divider between the thoracic and abdominal cavity,” says Professor Clemens. “I look at it as a unifier. It has this beautiful relationship between the upper and lower parts of the body.”

“People look at the diaphragm and think it’s a divider between the thoracic and abdominal cavity,” says Professor Clemens. “I look at it as a unifier. It has this beautiful relationship between the upper and lower parts of the body.”

Says Dr. Vranich, “I like to think of it as being right in the middle of everything. It’s right above your digestive system, so it massages your gut from the bottom down, and it affects your pelvic floor because it’s right below your gut. And then it affects your lungs, your heart rate, and your brain because it’s right underneath it all. Its effects ripple upward and downward.”

The systemic effects of the diaphragm are foundational to Jill Miller’s educational programming at Tune Up Fitness. “If I were to do a Venn diagram of the muscular structure of the body, I would say it’s organized around the diaphragm,” says Miller. Through fascial connections, the reach of the diaphragm extends from the base of the tongue, through the heart, spine, psoas, quadratus lumborum, and all the way down to the feet.3 “The diaphragm gives me a chance to teach about fascial interfaces,” Miller continues, “and how the little things affect the big things.”

Posture and the Diaphragm

The diaphragm’s impact on physiology depends on its mobility. A diaphragm with space to contract and relax at its full range contributes to homeostasis in the body by allowing the heart, lungs, gut, lymphatic, and circulatory systems to function optimally. A diaphragm that’s locked down thanks to poor posture or fascial restrictions can’t pump efficiently, and that slows down everything from blood flow to lymph to digestion.

Brian MacKenzie of SHIFT sees this all the time with his clients. “All mechanics and movement patterns center around how well I have access to the diaphragm. If my spine is not organized in order to utilize the diaphragm correctly, the diaphragm has to work harder because it’s out of position. I will compensate through my extremities to make up for that. We get caught in poor positions all the time, which inevitably leads to poor breathing patterns.”

Physical therapist James Anderson of the Postural Restoration Institute says simply, “there is a direct link between posture and breathing.”

“The body itself has a system of internal chambers that literally shape the body and determine the body’s form, its posture, and ability to function,” says Anderson. “At the heart of that postural system is the chest cavity where the lungs and diaphragm are. Below the chest cavity is the abdominal cavity, and then the pelvic cavity. And of course above the chest we have the cranial cavity. All of these internal cavities have a posture. And what the diaphragm and abdominals can do from the inside out to shape the internal chamber posture determines how you and I hold our body upright against gravity. In other words, we change posture from the inside out.”

Upper Crossed Syndrome

One way we’ve changed the internal posture of the chest cavity for the worse is our modern reliance on cell phones and computers. So much time spent looking at these devices with our heads forward leads to a phenomenon called Upper Crossed Syndrome, with chins out and shoulders rounded. “It constricts the diaphragm,” says Holly Clemens. “The abdomen gets pushed up and breathing becomes shallower. This is going to impact lung function. If you’re in the same posture all the time, you’re stagnant. The water’s not flowing, the synovial fluid’s not flowing, the motor neurons, the nerves, and the myofascia get locked in that way.”

James Anderson says respiratory dysfunction is rooted in this compromised mobility of the diaphragm. “A very important element of its function is to be able to assume the proper shape with the proper support around it. I would like the diaphragm to be able to make a full, complete transition from a proper dome shape, which is the relaxed state of the diaphragm, to a proper contracted state, which is the flattened state of the diaphragm, and then transition back to a full, relaxed dome. If it can make that transition between both of those postures, then the likelihood of optimal diaphragmatic respiratory function goes way up.”

Chiropractor and SOMA therapy instructor Jason Amstutz works with patients in a variety of ways— including the ELDOA method of postural exercises— to balance spaces in the body for better access to diaphragmatic breathing. “We work on changing the posture to balance out the tensions. Then you get a better functional diaphragm and you get more oxygen to your brain. Everybody feels better.”

So while everyone from your grandmother to your music teacher may have instructed you to “sit up straight!”, it turns out it’s more complicated than that. According to James Anderson, “Sometimes people are standing the way they are is because it’s how they’re best able to get air through their throat and lungs, all while holding their body upright against gravity without undue stress or strain on their chambers and system. And asking them to sit up straight to get what might look like ‘proper alignment’ from the outside can cause further compensation inside. So anytime someone tells you to hold a better posture, the question I would ask is ‘did it make your body feel better? Are you more relaxed and comfortable? Or did it make your body more tense and strained in your upper back, neck, and shoulders?’”

Physiology and the Diaphragm

This leads to another common consequence of a dysfunctional diaphragm— physical pain. “When the diaphragm isn’t working properly, it results in compensation patterns that only lead to more problems. Other muscles in the upper back and neck have to take over to expand the rib cage and help fill the lungs,” says Clemens. “And this can lead to chronic back and neck pain.”

In addition to posture and chronic pain, the diaphragm is important for the following reasons:

Balance

“If you’re breathing in an atypical way, for example with your shoulders, you’re off balance. There’s research that actually shows you’re less likely to have knee and ankle injuries if you’re breathing diaphragmatically.”- Dr. Belisa Vrasich

Digestion

“The esophageal pathway is through the diaphragm, so it also functions as a digestive muscle, in a sense. And when people have acid reflux, they have a failure of the esophageal hiatus to stay in proper tension. The rhythmic movements of the diaphragm also assists food’s movement through the guts.”- Jill Miller

Detoxification

“The pumping motion of the diaphragm is the way your body gets lymph, adrenaline, and cortisol out of your system. Everybody does these harsh detoxes, which can be brutal and sadistic. But lymph and the detoxification of your body depends on your diaphragm working well.”- Dr. Belisa Vrasich

Circulation

“Since the diaphragm surrounds the vena cava and aorta, it also acts as a cardiac synergist muscle. Not only does it stroke that vasculature and help move blood around, but it’s also a bed for your heart. The heart is sitting right on top of the diaphragm inside a fascial sack called the pericardium.”- Jill Miller

Emotional Regulation

“If you have digestive discord, if you have dysfunction with sleep, if you have mental anguish and anxiety and all of these physiological, mental, and emotional features that blend together to give a human being a really negative experience, you need the nervous system to turn that over. You need the nervous system to help all the other systems transition and be properly regulated. And the key to the nervous system doing that for all the other systems is respiration; the mechanical ventilatory process that we’re talking about.”- James Anderson, Postural Restoration Institute

Relaxation Response

The diaphragm is one of the primary keys to turn ‘on’ your ‘off’ switch by stimulating the parasympathetic features of the vagus nerve.”- Jill Miller

Just Breathe

T-shirts, coffee mugs, and Instagram posts abound with advice to “Just Breathe.” But is it that simple? What does it mean to just breathe?

Jill Miller organizes her Tune Up Fitness breath curriculum around three zones of respiration:

- Zone One: Abdominal

- Zone Two: Thoracic

- Zone Three: Clavicular

Dr. Vranich says our anthropological roots are in the fuller abdominal breathing. “There’s a difference when we look at primitive man. He would squat in a seated position more often, and as a consequence was more of a back breather. He had a bigger diaphragm, better lung capacity, and larger nostrils. So primitive man was a better breather.”

As we evolved, our lifestyle impacted our breath mechanics.

“Because of the way we stand and sit, we have a weaker diaphragm, smaller lung capacity, and more narrow nasal passages. Being seated without moving, and now having medium and small screens is affecting our breath,” says Vranich. “When your eyes are looking at something on a small screen and not moving, you’re concentrating in a predatory state. It’s similar to when animals are going after their prey; they take very small breaths and don’t move a lot. That’s what we’re doing in front of our computers and when we’re texting. The big movements and big breaths don’t happen.”

Even with our evolutionary history, Dr. Vranich says we still begin life as belly breathers, but that starts to change at about age 5 and a half years old. “We looked at 158 kids, and I thought there would be a difference in gender, but there wasn’t. And 5 1/2 was exactly the age where it changed from belly breathing. It’s when you go to school, when you start sitting, when you start becoming social. It’s also when you start taking tests, and you often start bracing your middle because of that stress.”

At the Postural Restoration Institute, James Anderson and his colleagues help people understand the importance of seeing the abdominals as equal partners in functional breathing. “A lot of people view abdominals as a core stability muscle, and then they view the lungs and diaphragm over on the other end of the spectrum as respiratory control muscles,” says Anderson. “The fact is, the abdominals are primarily designed to coordinate respiration. They’re responsible for reshaping the dome during exhalation, but they’re also responsible for controlling the flattening motion when the diaphragm contracts. In Eastern cultures they use the abs to move the ribs and diaphragm, and they have more core stability. In Western culture, we have mechanical dysfunction because we think about core stability as sit-ups and planks. I call it misuse of abdominals, and it’s prevalent across multiple disciplines; rehabilitation, performance, fitness. While we think that makes us stronger, it also makes us stiffer. We’re not sleeping better or moving better. We don’t have resilience, movement, variability, and function.”

How Do We Breathe Better?

It’s one thing to know what we should be doing to breathe better. It’s another to break old habits and create new patterns. To help people differentiate the muscles of respiration and identify where they are unconsciously gripping or using breath muscles inefficiently, Jill Miller created a self-guided exploration of the respiratory muscles through something she calls the diaphragm vacuum. In addition to exploring the anatomy of respiration, the diaphragm vacuum teaches us how to:

- Increase breath threshold, which has a psychological carry-over into daily life by helping us remain calm when stress takes our breath away.

- Quickly enter a parasympathetic state, the place of relaxation and restoration.

- Feel the connection between the diaphragm and ribcage from the inside out.

- Feel and map the myofascial connections between the diaphragm and the muscles it attaches to below the ribcage.

Strategies to Optimize Breath

Identify Stuck Spots

“Get in the best position you can get into, and start breathing slowly and controlled, all the way in, all the way out. See what you feel. Where do you find restrictions? Where do you feel soreness or pain? This is your indication of where you need work. Pain is there for a reason.” -Brian MacKenzie

Mobilize Tissue with Soft Tools

“Tune Up Fitness massage balls like the Coregeous and Alpha balls are phenomenal tools to help people identify their diaphragm kinesthetically. It helps with circulation, and promotes better sensory and motor output.” –Holly Clemens

Breathe through the Nose

“The most fundamental thing in understanding breath work is understanding the difference between nose breathing and mouth breathing. The nose almost tricks me into needing to use the diaphragm more because I don’t have this big wide hole to pull air in and offload the breath cycle out. So for the next four weeks, don’t open your mouth to breathe, no matter what you’re doing. Close your mouth to walk, run, lift weights, do yoga. Do it through all of these processes for the next four weeks because it’s a way to reorganize your physiology, and teach you what it’s like to draw a full breath in and out with your diaphragm.” -Brian MacKenzie

Focus on the Exhale

“Our culture thinks breathing is inhalation. The diaphragm’s drive when it becomes dysfunctional is to be inhalation driven, where it wants to contract all the time, contract too much, contract too early, contract too late. It becomes this annoying excessive tendency to over contract. And then you become hyperinflated. Your rib cage and lungs become overexpanded, and it prevents the diaphragm from assuming its full relaxed, dome posture on exhale. It can cause you to be anxious, short of breath, edgy. You can address some of that by focusing more on the exhale, and holding your breath at the end of that, to give your diaphragm a moment to adapt to the reality that it can be dome-shaped and supported again in its relaxed state.”- James Anderson

Develop a Breath Practice

“We need a breath practice to counteract how we spend all our time. The diaphragm is a muscle and if you want muscles to get stronger you have to work them to exhaustion. You have to work your breath muscles out separately.”- Dr. Belisa Vranich (Her book has targeted exercises you can do at home to strengthen muscles of respiration.)

Mix Up Your Movement Practice

“Don’t repeat the same thing all the time. People that live on a bike have their own set of problems. Yes, they have a great set of lungs, and a strong heart and legs, but they’ve created a rigid spine which doesn’t help them do a lot of other things. I’ve been good at lifting weights, but neglecting the fact that I need to stretch. Then I married a woman who’s a yogi and now I know why I wasn’t doing it. It’s a lot of work. It’s hard, but to really make a change, you’ve got to be doing a variety of things on a regular basis.”- Jason Amstutz

Make Your Breath Your Sixth Sense

“Cultivate an awareness of how your breath is intimately tied to everything you do. Befriend your breath as a barometer of your inner state; use it as a sixth sense and follow it like a curious breath scientist. Let your body be the lab and watch the natural actions of your breath as you encounter stress, joy, quiet, eroticism, and play. As you build that awareness, you’ll be more comfortable when you introduce breath exercises. Manipulate your breath with novel exercises that challenge its pace, as well as your physical body dynamics. This will expand your overall tolerance, and help you reap the rewards of opening your inner medicine chest.”- Jill Miller

Perhaps the most important thing to understand about the diaphragm is that its default design is to help all of the systems in your body function optimally, and you have the power yourself to engage it in a way that allows you to move and feel better.

“We’re missing the forest for the trees,” says Dr. Vranich. “We’re so busy scurrying around looking for some supplement or biohack that we’re not just looking at what’s right in our very own body. The diaphragm is smack in the middle of everything. It’s directly underneath your heart and lungs, and right above your gut, your second brain. So if that machine in the middle of our body isn’t doing what we want or taking care of us well, then it might be that we’ve excluded this terrifically important part of it, so it’s inhibited and not moving the way it’s designed. I tell folks ‘you’re taking all these vitamins and doing all these detoxes, but you’re not breathing right, which is foundational for everything else.’ This explanation may sound simple, but it really is the foundation of our health.”

For more on this topic, see Jill Miller’s new book Body by Breath.

The Diaphragm and its Four Cousins: The Other Diaphragms

Chiropractor and SOMA instructor Jason Amstutz defines a diaphragm as a series of fascial connections that are horizontal to the floor. While the respiratory diaphragm gets most of the attention, osteopathic medicine has identified four other diaphragms in the human body4:

- Tentorium Cerebelli: Separates the cerebellum from the inferior portion of the occipital lobes

- Floor of the Mouth: Muscular floor of the oral cavity that connects the right and left side of the mandible.

- Thoracic Outlet: The sternal bone and joints between the first two ribs and clavicle

- Pelvic Floor: The muscles and connective tissue underneath the pelvis, including the levator ani and coccygeus.

Endnotes

1. Oliver KA, Ashurst JV. Anatomy, Thorax, Phrenic Nerves. [Updated 2018 Dec 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513325/

2. Myers, Thomas. Body³: A Therapist’s Anatomy Reader, p. 68

3. Bordoni B, Zanier E. Anatomic connections of the diaphragm: influence of respiration on the body system. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:281‐291. Published 2013 Jul 25. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S45443

4. Bordoni B (April 23, 2020) The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Myofascial Relationships, Part 1. Cureus 12(4): e7794. doi:10.7759/cureus.7794

Fantastic article emphasizing the diaphragm as the key to unlocking the body’s full potential. Breath is truly the basic foundation of all movement, and we need emphasis on how to optimize it in any activity.

Amazing, clear article with a wealth of information that has taken me years to discover. Ty for putting this all in one place and explaining so well

I didn’t realize how much the diaphragm has such a strong impact on everything in the body until I read Jill Miller’s “Body by Breath” and started doing breathing exercises with the Coregeous ball. Even with yoga teacher training and 17 years of practicing yoga, I wasn’t breathing properly. Now I find myself noticing other people’s postures and related zones of respiration. I recently attended a course with an instructor who appeared to have breathing problems. He seemed to be breathing only in the Clavicular zone. He would take a big breath before speaking and his rounded shoulders would significantly hike up and his upper spine would round. I had to hold back from offering him some Yoga Tune Up® balls and exercises as it wouldn’t have been appropriate to offer an instructor in a safety recertification course.

Great article identifying the diaphragm’s important contributions to the whole body. Having taught classical Pilates breathing practices for 30 years, and being a student of Kundalini yoga for 5 years now has given me insight into the vital roles the diaphragm plays in our health and well being. Laying out the respiratory diaphragm’s relationship and influence to the many other body systems such as the cardiovascular, digestive and lymphatic systems is knowledge that everyone should be aware of.

It’s so easy to overlook the importance of breathing. Some people can get caught in a vicious cycle of anxiety that results in restricted breath that then leads to more anxiety and feeling out of control. Some people only really feel energized and alive when their sympathetic nervous system is activated. Mindful breathing is a powerful tool.

The diaphragm is such an important muscle. Many times when people are cued to take a breath, they immediately want to inflate their chest and tense up their necks. People are not aware that the diaphragm is the primary muscle of respiration – we end up using secondary muscles of respiration such as the scalenes to do all the work. This is connected with factors associated with the upper x syndrome…we tense up the scalenes which in turn elevate the shoulders, and the domino effects continues. I like how the blog brings importance to how the diaphragm has a role in organ function as well…just as it was written that maybe someone is told to sit up or stand up straight but maybe they cannot because the diaphragm is shortened – this would give us information on how to target the main issue. I love all the rolling techniques that Jill has on the diaphragm, so useful!

I like the part at the end about supplements and detoxes, that all the things we do for health don’t matter unless we’re breathing properly. I’ve recently started seeing a new therapist who’s connected all my lifelong health problems to a likely issue with my ability to breathe due to structural problems in the nasal passages, and I’m amazed to think how many things cascaded from that alone. It makes me realize how many ways our breathing can be impacted too. Postures, structural differences, stress, malnourishment of the muscles so the breathing muscles can’t fire properly, lack of awareness about anatomy and our own bodies’ functioning all can affect how we breathe and thus our overall health. I like the idea of the diaphragm as being a connector not a divider, as it really unites the body and if we tune into it and its needs and functions, can be the miracle cure we’ve been looking for inside a pill bottle all along!

As an Certified Breathe Coach– It’s always eye opening when we realize how growing in age changes our natural states, such as, belly breathing from birth. Overall, I have really enjoyed stretching my vagus, and diaphragm beyond what I had always imagined was mentally restrictive or impossible. Pushing passed my normal responses, and allowing myself to go in deeper while self soothing has increasingly brought awareness towards a very ‘controlled breathing pattern’, almost as a dynamic breath that stops-goes-stops-goes until the counts are completed. The quote that stuck out to me in this article is “Without it we would fall apart”, because this is just absolutely factual- without our breath there is no life, and with no life force well we wouldn’t be here. So, in short we breath to live, and while we live we breath! The breath is such a miraculous topic within itself for anxiety, releasing the psoas, and so much more! I LOVE breathwork, and believe in its powerful manipulation for assisting the body in reaching its homeostasis!

A diaphragm is paralyzed from an injury to the phrenic nerve. Does the parasympathetic vagus nerve help in any way? Is it so that a person can keep the body rhythm by stimulating the vagus nerve via the almost involuntary movement of the feet. (tapping in a rhythmic manner). Can this be addressed by yourself or ‘others’?

Please keep me posted

I appreciate the way Dr. Belisa Vranich discusses the importance of the diaphragm, stating how our bodies would ‘fall apart without it,’ I feel very pulled in to want to be a person who understands more about this muscle that we have not been taught to pay attention to until more recently. Definitely moved to check out her work and learn more, so thank you for that! Also–I hadn’t ever considered the pelvic floor to be a diaphragm, nor its connection to the diaphragm, and I appreciated learning about that connection–it makes a lot of sense! The importance on emotional regulation that was discussed here was an illuminating perspective that I need to reflect on more and I know I have experienced over time, however, not with necessarily understanding the mechanics of ‘why.’ Having taken the Breath and Bliss immersion with Jill Miller, I appreciate building on what I learned there through this article and I pick up on more each time I read it. I would like to stick the strategies to optimize breath list on my wall, and continue to share all with my students. Thank you for the compilation of so much diaphragmatic wisdom!

Magnifique article qui m’a aider à mieux comprendre l’intérêt du diaphragme dans ma vie quotidienne. Comment il agit sur mes intestins, mes émotions…

Je vais en prendre grand soin !

Excellent article, Suzanne. Smart and beautiful description of “the hub” and its diverse importance. I especially enjoyed the consideration of the abdominal group as a set of accessory respiratory muscles. Thank you for helping us see how the subconscious diaphragm hold can be so impactful. And how the breath sets us on the path towards wellness.

Love that quote: “People look at the diaphragm and think it’s a divider between the thoracic and abdominal cavity,” says Professor Clemens. “I look at it as a unifier. It has this beautiful relationship between the upper and lower parts of the body.”

Breathing is such a mystery and yet we forget all about it. So interesting things change at 5 1/2. When the parts of us start to brace for criticism, fitting in and brace against making mistakes. :'(

I do not think we are taught enough about this very important muscle. It was amazing to read what Dr. Vranich shared about how we are born as belly breathers and then when we begin schooling and are sitting, taking tests, etc. we start “bracing”. His acknowledgment of the mentality that many of us have about “core stability” might in some cases be doing more harm than good. It’s definitely a challenge for myself however it is something that I am working on. In my current teaching with young dancers, I am continually working on helping them become more aware of their breathe, the actions of the diaphragm and sensing how things feel and what might be going on when they breathe, etc. There is so much to learn about this magnificent connector inside the body! This is such a great resource.

This might be one of the most poweful posts I have ever read! I had no idea the diaphragm was connected to so many tissues related to the spine and its stability. The fact that the diaphragm connects to QL and psoas makes a lot of sense with what I feel and embody in my own body. ” A diaphragm that’s locked down thanks to poor posture or fascial restrictions can’t pump efficiently, and that slows down everything from blood flow to lymph to digestion.”

There is no question that I need to focus more on breathing. The exhalation is so important and is so neglected, but this is the space where the diaphragm gets to relax and settle in its space. It makes so much sense to spend time there to create more space to breathe efficiently while helping so many other tissues and systems to function optimally.

Thank you so much for sharing all this invaluable information. Breathing is so often overlooked as just “something we do” 20,000 times per day without thought. It’s amazing to think the diaphragm isn’t just our breathing muscle but plays a role in so many other things. So insightful and important!

I had no idea the effects that optimal diaphragmatic functioning has on the different cavities of the body as well as the negative effects that inefficient functioning can have on balance, digestion, detoxification, circulation, emotional regulation, relaxation and respiration. It pretty clear that by simply tapping into our primal ability to breathe, we can improve so much of our daily life. I love the

Everyone should take note and implement the “strategies to optimize breath” from this article. Those are practical and manageable actions that anyone could start implementing instantly, and guaranteed to improve the state of health and wellness.

This is amazing! I had no idea how critical the diaphragm is to so many other body functions and how connected it is to the tissues below and above. I am particularly interested in how to make a stronger diaphragm to help with digestion.

I was introduced to yoga when I was 17 and I found such a huge benefit in my body and my mental state. But it wasn’t until I found viniyoga that I discovered the power of breath. When I was introduced to this breath centric practice is when I realized how important my diaphragm was. This blog post just enlightened me even further of just how important this muscle is. I really loved the statement by Jill Miller, the diaphragm is a bed for your heart. I’m going to keep deepening my knowledge of this muscle and mapping my own diaphragm so I can share this with my students. Thank you.

Having dealt with mouth breathing most of my life (various issues), I was interested to make the connection between mouth breathing and a diaphragm that is not fully utilized due to “breathing through a bigger hole” (the mouth!).

The diaphragm is vital to our entire whole body wellness!! I was made aware of the necessity for my own dedication to my diaphragm functions several years ago and am so grateful for it. Since then I am constantly learning more about how connected and influential that muscle is. Thanks for the tips!!

The diaphragm vacuum is so challenging, even after reading everything on the diaphragm function it is so difficult to hold the breath and open the ribs at the same time. Breathing take practice.

Adult-onset asthma-no hills, no running, walking slowly, eating small amounts, diet restrictions, etc., do these exercises help, and can they be modified to begin slowly?

I have a variety of health issues including forward head posture from a flare up in my neck. I was directed to your website for more information on posture and breath. Thank you!

I learned a great deal about the diaphragm and the diaphragm vacuum in this article. I never realized how using the computer and texting affected our breathing. Amazing!

This article is really comprehensive and informative. I have learned a multitude of things about the diaphragm. Thank you

Very great article! I want to learn more about this muscle, because many muscles stiffness start from the bad breathing.

So interresting ! So much informations ! I will have to read it again for it to sink in. I’ve been practicing the diaphragm vaccum. It’s harder than it seems but, ho boy, it felt great. I will practice it for sure

It’s incredible to see the power of the diaphragmatic respiration. The coregeous ball really helped me with that. It’s true that when I’m in front of a computer for a long time I don’t breath as profound as normally…

So we all started with an abdominal breathing and we lost it with the society life. We need to learn it back… Thanks to you for this education!

YTU

This answers so many questions for me. I have many symptoms that all relate to the diaphram. I look forward to learning more and participating in these type of sessions.

As an RMT I see people daily dealing with upper cross syndrome. I try my best to explain to them all the benefits diaphragmatic breathing has and how their current posture is limiting that but it doesn’t always seem to stick. This article explains it a lot more eloquently that I ever could and will have to start recommending my clients to read it.

I truly underestimated the role of the diaphragm in total health and wellbeing. Fake thoracic breath in uddiyana bandha and rolling on the Coregous ball really helped relieve tension in my core, enhanced my breathing and relax! Thank you for sharing!

Thanks for a brilliant article! I especially took notice of this sentence: “it can result in adhesions to the diaphragm from surrounding organs”. I am trying to get better from chronic disease, and this ressonated a lot. I have a mild pectus excavatum, and when I breathe in deeply, the chest bone goes further inwards, and it feels as if it drags my heart downwards. Is it possible that my heart could be stuck to the chest wall or the diaphragm in some way? And if so, is there anything I can do? Any suggestion is very welcome!

Hello. Fascinating stuff. As healthcare practitioners, I think we all know this on some level and then (ashamed to say myself) we tend to put it on a back burner because another ‘approach’ has come along. I am interested to know how I can apply, modify or adapt this vital information to children with neuromotor conditions (cerebral palsy, for example) and especially with people who may not be able to directly follow verbal instructions (i.e., “breath into my hand…”). Is there a way to improve diaphragmatic function and thus the rest of the body by non-verbal means or by physical cues? I have not done a lot of detailed bodywork continuing education (like myofascial release) and wonder if this is my missing link to helping these kiddos improve their posture and function. Thanks in advance.

Very well written! One point they did not mention: The 4 horizontal diaphragms of the body (pelvic, respiratory, thoracic, cranial) are connected by a vacuum, thus, whenever you hiccup, sneeze, laugh, cough, burp, or fart, all 4 sphincters open and shut simultaneously, ever so slightly, and that’s why you might have more than 1 orifice expelling.

In my bodywork, I focus A LOT on releasing the respiratory diaphragm, which is the gateway for lymphatic drainage & debris to flow downwards, from the head & chest, emptying into the colon. If it’s tight, posture restricted, has damage from surgery, injury adhesions, or other blockages, the lymphatic system cannot do its job properly, and stagnant fluids buildup in the chest, and ultimately lead to sinus, throat or headache issues, backing up, up, up. RELEASE YOUR DIAPHRAGM with Deep Breathing. Today!

Interesting article

This is a pretty awesome summary of all-things diaphragm. I teach anatomy, with cadavers, and one thing that has intrigued me that you didn’t mention is the overlapping attachments of the central tendons of the diaphragm with psoas and quadratics lumborum on the anterior face of the lumbar vertebrae. Psoas and QL are such crazy important muscles, and the spot where their origins overlap with diaphragm insertions looks like some crazy hub or pivot point for the upper and lower bodies…mighty close to the adrenal glands too. Really curious to know what your thoughts are on this!

Thanks for sharing such a detailed article here. Yoga has a lot of breathing exercises which are very effective.

My name is Janet, a reiki practitioner and student of meridian acupressure in Mexico and the United States. I am also experimenting with the use of therapy balls on myself and want to solve some of my issues with pressure from therapy balls.

So interesting! I was very interested in learning the role of the diaphragm not only in breathing but also in psychology, balance, digestion, detoxification, circulation, emotional regulation, relaxation respond. And you are right; Just breathe is not that simple, this is why we do breath work.

I thoroughly enjoyed this article. I’ve forwarded it on to numerous clients. I provide Rosen Method bodywork which is connected to observing where the breath is, and is not, moving in the body. Many times clients are completely unaware they are ‘holding their breath’ so to speak, and their diaphragm is hypertonic, relating to further aches and pains throughout the body. Or vise versa, an injury or trauma forced them to hold their breath to deal with pain. The human body is fascinating.

Lot’s of good stuff here. Wish I’d seen it put together in one tidy place like this 15 years ago! Thank you a million times over for this. I’m sharing it widely.

grokking the diaphragm was a breakthrough thing for my decade long working out of back and nerve pain. My 5-6 year recovery quest working the Egoscue Method (which saved my life! not hyperbole to say so).

However, I had hit a plateau in that recovery working from 2003 until I came upon Kelly Starrett’s MWoD in about 2011 and subscribed. The addition of PNF to Egoscue type work as well as Kelly’s work with bands and ball got me increasing mobility and reducing reinjury. Then one day, I just started to blow through the plateau when Jill Miller and Kelly Starret collaborated on a “gut smash” video. Then the Roll Model book came along, Yowza! Pure anatomy pR0n. Really filled in a lot of missing understanding

So Jill, No irreverence meant when I say I thank God for you!

I really enjoyed reading the article. I was stunned (but yeah it made so much sense) to read about the research that concluded that belly breathing changed around 5 and a half years: about when kids go to school, sit and take tests. Education about breathing, posture and respiratory diaphragm should therefore be introduced before that age to our children!

I did not know that the diaphragm plays so many roles in our body function. Amazing!

Wow it’s fascinating to see the impact of the diaphragm in the whole body. I really like the comparison with the umbrella.