During my typical day as a teacher and graduate program coordinator on a college campus, I have seen disturbing ergonomic habits wherever I look, whether in my building or while moving across campus.

Many young people do not yet feel the accumulation of wear and tear they are creating in their poor, repetitive ergonomic habits. So they seem less concerned than my older friends.

It is troubling to contemplate how these habits will impact this age group earlier than past generations, who were more active before and during their college years.

This issue was my inspiration for developing a new Ergonomics course for SUNY about personal health components of ergonomics. It covers how multiple body systems are impacted by our habits, and offers self-care hacks to mitigate the stressors and potential damage.

The best news is that techniques for recovery and injury prevention can be learned. We can choose to be the masters of our technology-driven, sedentary world and optimize our habits to feel our best. Embedded in this post you will find practices to take the essentials of ergonomics into your own hands.

The Pitfalls of Our Modern, Cushy World

Health among deskbound populations is impacted by our modern habits of excessive screen time in chairs, or with limited body movement. This is often coupled with cognitive demands while using modern technology devices, now ubiquitous in the workplace and during personal time.

You may be reading this and think, “but I exercise regularly, so this does not apply to me.” If so, please read my article about repetitive motion, exercise habits, and how a lack of variety of movement is also a factor.

Those of us who do not sit at a 9-to-5 job at a computer may also think, “thank goodness this is not me.” However, you may be unaware of how much time your eyes are focused upon your smartphone, often in a gripped and hunched position.

The use of technology, the force of gravity, and today’s environment impact our muscle movements and strength, physical work capacity, and stress. This, in turn, impacts metabolic outcomes, deconditioning, the risk for musculoskeletal injury, and wellbeing.

Personal ergonomics are comprised of our biomechanical positioning habits (always loaded by gravity), repetitive motions related to our particular lifestyles, how we hold and process stress in our bodies, and “cognitive ergonomics” which address the psychological and mental impact of our physical environment on our whole system.

Statistics show epidemic levels of musculoskeletal disease (MSD), repetitive strain injuries (RSIs), and the need for better stress management. These issues are further reflected in our pain medication and Rx addiction crises.

There are warning voices regarding damages of our movement-limited lifestyles such as the teachings of my mentor Jill Miller, Katy Bowman, and others. Yet it seems that prevention education for self-care is still lacking; it is not mainstream at schools, nor workplaces yet.

Most US health insurance will “fix broken people” but pays little toward self-care and prevention. Individuals must seek out their own self-care education through yoga classes or other self-funded extra-curricular activities.

The fantastic news is that it is possible to learn do-it-yourself techniques to improve your ability to manage and navigate the pitfalls of our modern cushy world.

DIY Techniques for Good Ergonomics on the Workplace

“Ergonomics” and “human factors” include the interaction of humans with their environments. It is a huge topic for which entire books are written. Today, I will discuss body positioning, along with a few key interrelated elements of ergonomics that do not get enough attention, yet impact health profoundly.

Follow along with the practice exercises to experience this learning in your own body.

Exercise #1: CheckIn on Seated Ergonomics

Sit at your desk the way you normally would. Notice how your body feels–hips, spine, neck, etc. Use this as a baseline to check in on how you typically sit.

The science behind position, loading, and movement:

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are injuries or pain in the human musculoskeletal system, including the joints, ligaments, muscles, nerves, tendons; the structures that support limbs, neck, and back. MSDs are the leading cause of physical disability in the US.

The top three (of four) most commonly reported medical conditions are chronic low back pain, joint pain, and disability from arthritis. Once upon a time, such conditions were usually a result of strenuous manual labor like heavy lifting, but now we see many people sustain these injuries just by sitting at desks all day.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention warns us that prolonged sitting can reduce blood flow, increase our risk for blood clots, irritate nerves, and even cause “micro-trauma” to muscles. But surprisingly, it is not just “regular folks” who are impacted by too much sitting in our modern world.

Even research on younger adult athletes shows that as high as 30% report low back pain which agrees with more recent studies showing that “very active” people, as well as the “sedentary” groups, have a greater risk for chronic diseases than we previously thought, due to too many hours of stillness.

DIY Ergonomics Technique: Pelvic positioning

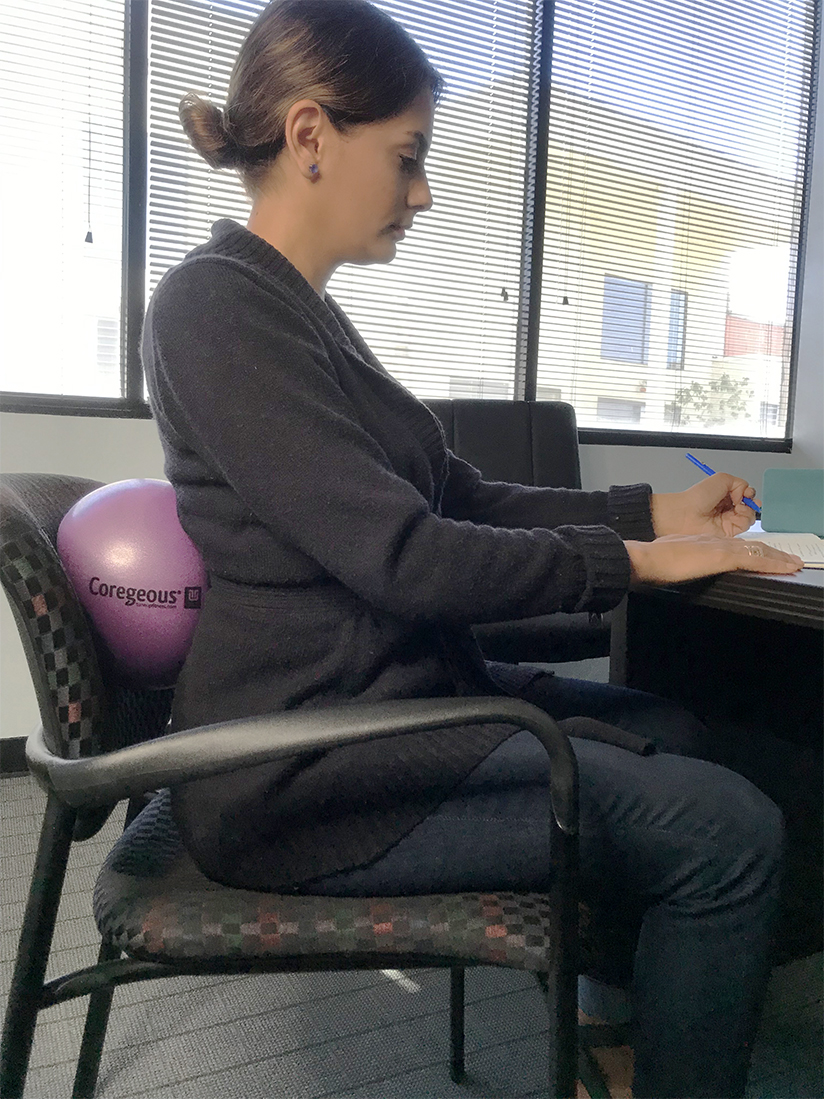

To begin to sense the position of your pelvis and better understand your typical pelvic alignment, try this exercise sitting on a Coregeous® sponge ball on a low bench or chair. This can also be done on a larger exercise ball.

Exercise #2: Pelvic Tilts Sitting on Coregeous® Ball

- Rest your pelvic floor straight down on the sponge ball

- Anterior and posterior tilt your pelvis by curling your tailbone under, then tilting it up

- Next, rock your hips right to left several times, you could also circle your hips

- Sense all the different possible positions of your pelvis and how they relate to the position of your spine

- Finally, try to find an even position where your pelvis is perfectly neutral

How technology impacts stress-sleep-relaxation:

Now consider “cognitive ergonomics.” This is how mental stress and body tension, including the use of technology, impact the nervous system, sleep, and more. The combination of inactive physical habits together with nonstop mental stimuli from technology-driven devices results in a hazardous physical-mental strain that leads to a greater incidence of chronic disease, now seen at younger ages.

Research shows that our ever-increasing use of computer screen devices at work, for school and for pleasure (often late into the night), results in general fatigue, aches, and stress. This excessive “screen time” is linked to an elevated state of ‘fight or flight’ of our nervous system and is related to sleep deprivation which also raises our health risks for higher anxiety, anger, daytime exhaustion, problems focusing attention, mood swings, and even lower grades among students!

Being in a chronic state of ‘fight or flight’ negatively impacts our emotional balance well-being and actually most systems in the body. This primal stress reaction was meant to quickly save us from danger if we needed to run from a saber-toothed tiger. But, nowadays, our environment triggers us 24-7-365, and damage occurs over time if our body tries to maintain the cascade of stress hormones.

First, adrenaline kicks off a faster heart-rate and breathing and shunts blood away from our guts to our arms and legs to run, while conserving immune system power (because using energy to fight or flee is more important in an “emergency”).

The problem is that our modern “danger” is simply a screaming customer, an argument with a stranger on social media, or a traffic jam. This chronic state of stress not only impacts our cardiac and respiratory systems but also our digestive system and immune function to name a few.

Over time, this vicious cycle of stress, sleep deprivation, too much screen-time, leads to more moodiness and more tension (body and mind). It is associated with many serious long-term problems because it can actually change our brain chemistry and create tissue damage. These physiological changes can lead to sleep disturbances, insulin resistance, diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure.

DIY Ergonomics Technique: Calm the Body Through the Breath

These techniques will help relax tense respiratory muscles that could be contributing to stress, overwhelm and sleep issues.

Exercise #3: Roll Out Stress Muscles of Respiration

Using one Roll Model® therapy ball, ease up the subclavicular respiratory muscles with deep-tissue myofascial self-massage at the wall.

- Put therapy against yoga block, or doorframe

- Lean your body weight into the therapy ball placed just under your collarbone

- Take several breaths, then slide your body right and left and wiggle your shoulder up and down

- Plug the therapy ball in one place and move that arm up and down

- Step away and notice how your shoulder feels different

Breath and ribcage mechanics:

Our statue-like habits, including slumping for long periods of time, limit the way our ribs were meant to move which alters normal breathing patterns, which in turn trips a switch in our nervous system. When our brain detects the shallow obstructed breath pattern, it thinks we are in trouble and signals a “high alert” and keeps us in a stress state (“fight or flight”) until we fix it.

In addition to poor breathing creating stress to our nervous system, we also increase our chances for backaches and create a major “amnesia” in our spine’s ability to detect body position (proprioception). This impacts our quality of movement and stiffness.

But the great news is we can easily “hack” into our primal stress response and this lousy series of events by creating relaxation and better well-being when we practice slower, deeper breathing habits.

Exercise #4: Breathe into Sternum, then Massage the Circumfrence of the Diaphragm

Using a Coregeous® sponge ball, stand at the wall.

- First, place the sponge ball at your sternum, stand upright, and breathe deeply into your chest

- Feel the sternum press into the sponge ball on inhale, and pull away on exhale

- Stay for several rounds of breath

- Next, place the sponge ball at the line of your respiratory diaphragm, where your front ribs meet

- Interlace your hands behind your head and breath into the sponge ball, sensing it

- Then, rock right to left and make a full loop tracking the circumfrence of your diaphragm

- Do this several times

- Finally, rest with your back against the sponge ball and take severall deep breaths

Aside from back and neck pain, our slumping and stuck postural habits not only cause somewhat shallow breathing, but specifically, we do not exhale properly. Poor exhalation perpetuates the “fight or flight” response which keeps us stressed out. The sad cycle of poor posture, causing aches and overall stress, is reinforced by continued shallow breathing patterns and poor ribcage movement.

Unfortunately, there is even more bad news about this state of chronic tension that involves our heart health. A measurement called heart rate variability (HRv) assesses the variation in time between each heartbeat and is a known marker of cardiovascular health, vagal tone (relaxation capability), and is a tool for predicting disease.

Decreased HRv (less variability of time between heartbeats) is associated with chronic diseases that include diabetes, coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure. Increased HRv (more variability between heartbeats) shows an ability to manage our sympathetic or “fight or flight” reactions and to switch gears. It is considered a marker of enhanced parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) nervous system health which leads to greater wellbeing.

Good news is that relaxation practices promote a more “parasympathetic state” known as “rest and digest” (versus “fight or flight”), so we can improve our HRv or vagal tone. The phrase “vagal tone” refers to the vagus nerve, a major nerve in our upper body, that controls our heart tension and heartbeat.

When we practice breathing exercises, we improve overall relaxation of our body’s environment for wellbeing and prevention of chronic disease.

The exercises in this post will help relax the nervous system while improving posture and breathing.

Exercise #5: Expand the Intercostal muscles

Stand at the wall to perform boomerang at the wall. This will help lengthen the ribcage and stretch soft-tissues that will help break the tension pattern and increase your volume of breath.

- Stand sideways at the wall

- Place your bottom hand against the wall, fingers up, approximately at waist height

- Reache the opposite arm toward the ceiling and internally rotate the shoulder so the palm faces away from the wall

- Sidebend toward the wall and place yoru fingertips against it

- Elongate through the side-body–especially the ribcage

Exercise #6: Seated Posture Support

- Sit in your office chair with a Coregeous® sponge ball at the line of your respiratory diaphragm (at the lowest ribs)

- Create impeccable poise through your torso while sitting evenly on your ischial tuberosities

- Keep your head level and gaze straight ahead with your eyes

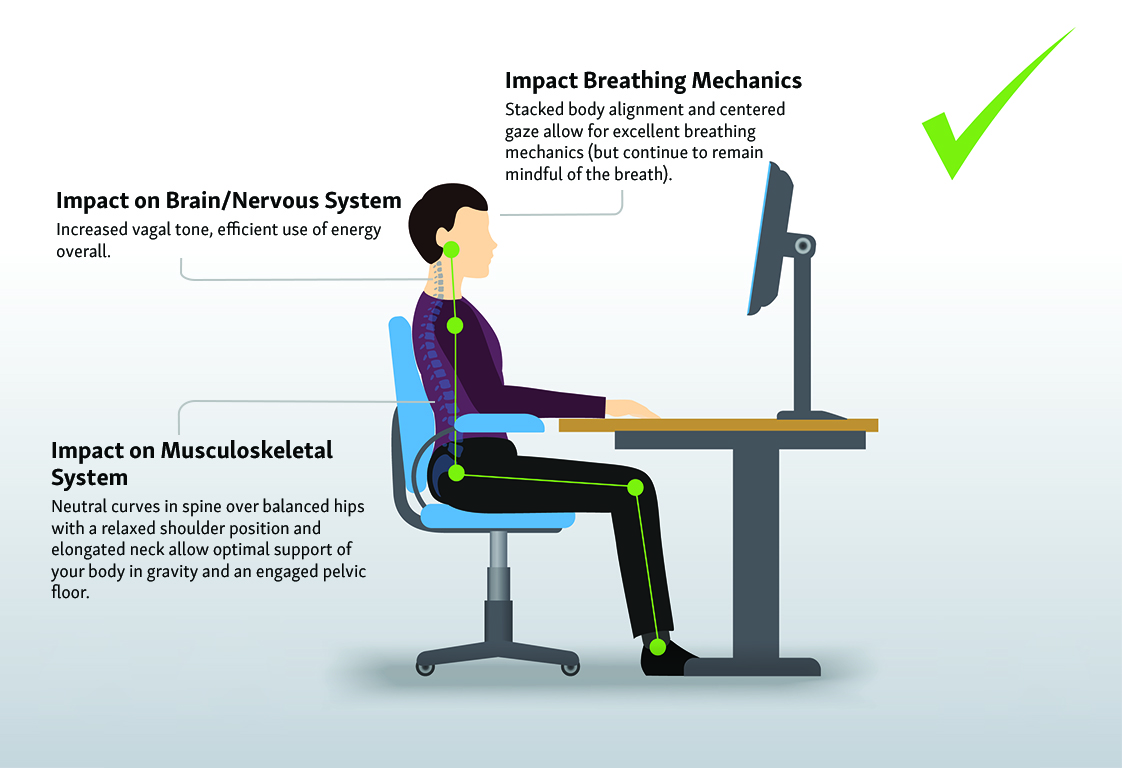

Exercise #7: ReCheck on seated ergonomics

Sit at your desk again. Notice how your body feels different after these exercises – hips, spine, neck, etc. Attempt to embody the below alignment points.

Final Thoughts on Maintaining Healthy Ergonomics

This author’s short review of basic mechanical loading of the sedentary body illustrates how static positioning can impact ALL body systems including mental stress, cardiac, neurological and musculoskeletal health.

But, there is more emerging research showing that our chronic lack of movement and limited body use may be associated with other chronic conditions including cancer, diabetes, obesity and digestive issues.

While this article offers a brief “survivor’s guide” for sitting and electronics use, the truth is we need to move all day long. It is movement, NOT sitting and stillness, that is wired into our DNA and our primal body-systems design.

Our modern habitat deprives us of the movement variety for which our bodies were created. After 200,000 years of daily movement variety required for survival, humans have wreaked havoc on their health by use of “convenience” and modern “built environments” in only a few short decades!

In our present-day carseat, couch potato, desk-chair habits, entire body segments may go unused during a day (or more). But, for good health and wellbeing, ALL of our body’s cells and body segments require some mechanical movement pressure or vibration, not just a (blood) supply of oxygen, food-glucose, and CO2 removal.

Good self-care dictates that we continue to learn more about ergonomics and movements that our bodies crave (and rarely practice) in a healthy movement diet. Tune Up Fitness friend, Katy Bowman is an expert in body mechanics and also writes easy-to-read, scientifically sourced information about movement as a required daily “nutrient” of our cells and there is also a rich collection of information in the Tune Up Fitness library, DVDs and YouTube page.

Related Article: Springtime in Your Joints: 5 Ways to Preserve Joint Health with Jill Miller

Learn more about our Therapy Ball Products and Programs

Interested in video and blog content targeted to your interests

Resources:

Bono C. (2004). Low-back pain in athletes. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 86-A(2):382-96.

Bordoni B. & Zanier E. (2013) Anatomic connections of the diaphragm: influence of respiration on the body system. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 6; 281-291.

Bordoni, B. & Zamier, E. (2014). Skin, fascias, and scars: symptoms and systemic connections. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 7; 11-24.

Braun, S. (1990) Respiratory Rate and Pattern. In Walker, H., Hall, W. & Hurst J. (Eds.), Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations, Third Edition (Chapter 43). Boston, MA: Butterworths Publishing. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK365/ (Accessed on 5/31/2016).

Brumitt, J. (2010). Core assessment and training. Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL

Burg, J., Wolf, O. & Michalak, J (2012). Mindfulness as self-regulated attention; associations with heart rate variability. Swiss Journal of Psychology 71; 135-139. Available at: http://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/abs/10.1024/1421-0185/a000080 (Accessed 6/11/2016)

Calamaro, C., Mason, T.B. & Ratcliffe, S. (2009). Adolescents Living the 24/7 Lifestyle: Effects of Caffeine and Technology on Sleep Duration and Daytime Functioning. Pediatrics, 123(6); pages. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/123/6/e1005.short (Accessed on 5/22/2016).

“CDC – NIOSH Program Portfolio : Musculoskeletal Disorders : Program Description”. www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

Department of Health and Human Services (NIOSH) Publication No. 2017-131 Using Total Worker Health® Concepts to Reduce the Health Risks from Sedentary Work. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/wp-solutions/2017-131/pdfs/2017-131.pdf (Accessed 6/22/2019).

Depp, C. & Jeste, D. (2006) Definitions and Predictors of Successful Aging: A Comprehensive Review of Larger Quantitative Studies. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(1); 6-20.

Dunckley, V. (2015). Reset Your Child’s Brain: A Four-Week Plan to End Meltdowns, Raise Grades, and Boost Social Skills by Reversing the Effects of Electronic Screen-Time. Novato, California; New World Library.

Givi, M. (2013). Durability of effect of massage therapy on blood pressure. International Journal of Preventative Medicine, 4(5); 511–516. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3733180/#ref26 (Accessed 6/3/2016)

Hodges, P. (1999). Is there a role for transversus abdominis in lumbo-pelvic stability? Manual Therapy, 4(2):74-86.

Hodges P., Gandevia S. & Richardson C. (1997). Contractions of specific abdominal muscles in postural tasks are affected by respiratory maneuvers. Journal of Applied Physiology, 83(3);753-760.

Hughes, J., Fresco, D., Myerscough, R., van Dulmen, H., Manfred ; Carlson, L., Josephson, R.(2013). Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Prehypertension. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(8); 721-728.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are. New York: Hyperion.

Kang, H., Lee, H., Shim, J., Shin, Y., Park, B. & Lee, Y. (2010). Association between screen time and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents in Korea: The 2005 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 89(1); 72–78.

Kendall, F., McCreary, E. & Provance, P. (1993). Muscles Testing and Function (4th ed.) with Posture and Pain. Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD

Kjaer, M., Langberg, H., Heinemeier, K., Bayer, M., Hansen, M., Holm, L., Doessing, S., Kongsgaard, M., Krogsgaard, M. & Magnusson, S. (2009). From mechanical loading to collagen synthesis, structural changes and function in human tendon. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 19, 500-510.

Landers, M., Barker, G., Wallentine, S., McWhorter, J. & Peel, C. (2003). A comparison of tidal volume, breathing frequency, and minute ventilation between two sitting postures in healthy adults. Physiotherapy Theory & Practice, 19;109–119 Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09593980307958 (Accessed 5/30/2016)

Langevin, H., Bouffard, N., Fox, J., Palmer, B., Wu, J., Iatridis, J., Barnes, W., Badger, G. & Howe, A. (2011). Fibroblast cytoskeletal remodeling contributes to connective tissue tension. Journal of Cell Physiology, 226(5); 1166–1175.

Lin, F., Parthasarathy, S., Taylor, S., Pucci, D., Hendrix, R. & Makhsous M. (2006). Effect of different sitting postures on lung capacity, expiratory flow, and lumbar lordosis. Archives of Physical & Medical Rehabilitation, 87(4);504-509.

Martini, F. & Bartholomew, E. (2010). Essentials of anatomy and physiology. 5th ed. Pearson Education; San Francisco, California.

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tiller, W., Rein, G. & Watkins, A. (1995). The effects of emotions on short-term power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. The American Journal of Cardiology, 76 (14); 1089-1093.

Miller, J. (2014). The Roll Model®: The Roll Model: A Step-by-Step Guide to Erase Pain, Improve Mobility, and Live Better in Your Body. Victory Belt Publishing: Las Vegas, NV.

Mirams L., Poliakoff E., Brown R. & Lloyd, D. (2013). Brief body-scan meditation practice improves somatosensory perceptual decision making. Consciousness and Cognition 22 (2013) 348–359. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22889642 (Accessed 6/11/2016)

Moore, M., Brown, D., Money, N. & Bates, M. (2011). Mind body skills for regulating the autonomic nervous system: Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (www.dcoe.health.mil), V.2

O’Sullivan, P., Grahamslaw, K., Kendell, M., Lapenskie, S., Möller, N. & Richards, K. (2002). The effect of different standing and sitting postures on trunk muscle activity in a pain-free population. Spine, 27(11);1238-1244.

O’Sullivan, S. & Schmitz, T. (2001). Physical rehabilitation: assessment and treatment (4th ed.), Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company.

Owen, N., Sparling, P., Healy, G., Dunstan, D. & Matthews, C. (2010). Sedentary Behavior: Emerging Evidence for a New Health Risk. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Dec; 85(12); 1138–1141. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2996155/ (Accessed on 5/23/2016).

Park, K. & Oh, J. (2014) Influence of thoracic flexion syndrome on proprioception in the thoracic spine. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 26; 1549–1550.

Ryff, C., Singer, B. & Dienberg Love, G. (2004). Positive health: connecting well-being with biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences, 359; 1383–1394. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1693417/pdf/15347530.pdf Accessed on (5/22/2016).

Sakakibara, M., Takeuchi, S. & Hayano, J. (1994). Effect of relaxation training on cardiac parasympathetic tone. Psychophysiology, 31: 223-228

Schleip, R. (2003). Fascial plasticity – a new neurobiological explanation, Part I. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 7(1); 1-19.

Sharma, G. & Goodwin, J. (2006). Effect of aging on respiratory system physiology and immunology. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 1(3): 253–260.

Somers, V., Mark, A. & Abboud, F. (1991). Interaction of baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in normal humans. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 87, 1953-1957.

Sroykham W. & Wongsawat Y. (2013). Effects of LED-backlit computer screen and emotional selfregulation on human melatonin production. Proceedings of 2013 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS), Osaka, Japan; July 3-7, 2013.

Stauss, H. (2003). Heart rate variability. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 285( 5); R927-R931. DOI: 10.1152/ajpregu.00452.2003

Sudsuang, R., Chentanez, V. & Veluvan, K. (1991). Effect of Buddhist meditation on serum cortisol and total protein levels, blood pressure, pulse rate, lung volume and reaction time. Physiology & Behavior, 50 (3); 543-548

Tang, Y., Holzel, B. & Posner, M. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews; Neuroscience, 16(4):213-225.

Tham, S, Lewandowski Holley, A., Zhou, C., Clarke, G., & Palermo, T. (2013). Longitudinal Course and Risk Factors for Fatigue in Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Sleep Disturbances. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(10); 1070–1080. Available at: http://jpepsy.oxfordjournals.org/content/38/10/1070.full.pdf+html/ (Accessed on 5/22/2016).

United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS), Third Edition, 2014. Rosemont, IL. Available at: http://www.boneandjointburden.org. (Accessed on 5/22/2016).

van der Zwan,J., de Vente, W., Huizink, A., Bögels, S. & de Bruin, E. (2015). Physical Activity, Mindfulness Meditation, or Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback for Stress Reduction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Applied Psychophysioly and Biofeedback,40(4); 257–268.

Wang, D., Rao, H., Korczykowski ,M., Wintering, N., Pluta, J., Khalsa, D.S., Newberg, A.B. (2011). Cerebral blood flow changes associated with different meditation practices and perceived depth of meditation. Psychiatry Res. 30;191(1):60-7.

Womersley L. & May S. (2006). Sitting posture of subjects with postural backache. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics, 29(3); 213-218.

Workplace Wellness: The Role of Ergonomics and Movement (Sep 01, 2017) https://ohsonline.com/Articles/2017/09/01/Workplace-Wellness.aspx?Page=2

The lack of prevention of back pain is bewildering to me. I’m curious how many days of work are lost due to back pain in the US and how much lost revenue. You would think more measures would be taken to avoid this. I tried the exercises and I feel more aware of how my spine is stacked, where my shoulders are in relation to my spine. A lovely practice – thank you!

I did the exercises along with the article and noticed how relaxed I started in my sitting posture and how much more aware I am now after the practice. It’s easy to forget and get lazy on our sitting postures. Even as I type this, I realize my laptop screen should be higher for proper alignment of my cervical spine. This article inspired me to go move my body now. A movement break to help my body run more effectively.

I’m glad this is being talked about more because I see the effects of extensive sitting in my massage practice so much and most people don’t know that’s what it is from! It’s so helpful to firstly be aware of what our chronic patterns of stillness or movement are doing to our bodies and then to also have tools to remedy the issues they cause. Many people are unaware of the tension in the chest because they only feel the pain in their back and shoulders, so I like having the roll outs to offer so they can feel the difference!

I was always told that sitting was bad… but never understood why. Thank you for providing such an easy to read and easy to understand medical description of the affects of sitting on all areas of our well-being. I will be sure to keep all these tools and suggestions in mind for myself and share them with everyone I know!

Bref, l’importance de bouger et de bouger de différentes façons!

merci pour ces exercices intéressants que je vais mettre en pratique !

Merci pour ces exercices! Nous devrions tous avoir dans notre porte document…sac à dos ces balles et prendre quelques temps d’arrêt dans la journée pour changer notre position au travail devant l’ordinateur et se masser avec les balles. Nous avons moins conscience des ravages lorsque nous sommes jeunes, mais c’est à ce moment que nous devrions développer ses nouvelles habitudes.

Le travail de bureau est le pire ennemi du corps, chaque jour je vois ses ravages sur mes clients. Avec la covid, le temps d’écran a explosé, sans parler des postes de travail non ergonomiques. Merci pour ces astuces qui permettent de replacer le corps suite aux longues journées devant l’ordinateur.

As someone who has a desk job and associated lower back pain, I think this is a great article with practical examples of how to improve one’s body awareness and posture while working at a desk.

I always get asked “what is the best desk set up?” I always answer with movement and awareness of your habits. This article is great and nails that! It is sad to think our healthcare system pays for what’s already broken in our bodies vs self care. This was a great read and really shed some light on important positions with easily digestible information. Thanks so much for sharing

Thank you for detailed explanation on how prolonged sedentary position and modern day habits affect our long term health. Many people prioritize only on maintaining “good seating posture”. This article further emphasized the need to also have good dose of daily and varied movements.

There must be a body sensor app by now that can tell you when your posture is getting worse while sitting and working at a computer. While it seems simple to get into correct alignment (e.g., neutral pelvis) it is hard to stay in it as we get absorbed into brain focused work. I will definitely try the Courageous ball exercises and see if that helps with paying more consistent attention to sitting/working body position.

I appreciate the authors presentation of the exercises that will increase mobility, breath, postural activation, relief and counterbalance to “office ergonomic” tasks… Some thoughts are that there is often an idea that focuses on the person being responsible (as they should be) to preparing/recovering their body to be resilient for the tasks at hand – One of the important things (there are multitude of approaches) about ergonomics is recognizing that the task must fit the capacity of the human – so if someone is asked to do a task that the only way they can do it is to flex their neck and elevate their shoulder girdle for hours (working on a laptop on a too tall of a surface) this person will have overloaded, tight, weak muscles and mechanical imbalances – no matter how much rolling, stretching, strengthening, breathing, they do…..

One of the populations I work with are the desk workers of corporate America and I love how you pointed out that even though many of these individuals exercise daily, they are still sitting way too much with less than ideal posture and developing compensations. These are some wonderful simple exercises I can’t wait to try out on my next corporate group class to help improve their postural awareness while sitting at the desk. I also found it super interesting to learn more about the role of heart rate variability in health beyond cardiovascular recovery from intense workouts – thank you for the citations to a wealth of information in the articles that helped you write this.

I am a High School teacher in the tech neck age and I see all kinds of posture issues. I actually go through proper alignment and posture with my students both sitting and standing. A lot of students really enjoy when I do wellness Wednesdays. I also liked the suggestions for creating a more ergonomic workspace. I never thought about using the corgeous as a lumbar support. I don’t sit that often, but when I do, I’m going to try that from now on!

It was great to learn that increasing heart rate variability is important to minimize risk of disease. It was also good to connect this idea with what are unrecognized stressors in our sedentary life and how they can keep our “fight or flight” response on for prolonged periods, decreasing our HRv. It makes me want to engage in more deep long exhales during my restful periods.

A fascinating and well-informed article to remind us all of the importance of maintaining good posture when working. After a year of suddenly having to work from home in less than ideal setups, I think a lot of people could benefit from this.

Easy exercises to introduce in a day!

Thank for this article! Indeed, modern ergonomics masks the human body. We adapt too much a sedentary lifestyle. It’s time to get up, move and roll with the YTU balls!

Thank you for the tips. I will try the pelvic tilts and the seated posture support. I already integrated some rolling pause at work and it make a huge difference. I agree that we really need to bring awereness into our posture. For sure when we are too focus for a long time we slump..

This article is a self care gold mine! Now more than ever during the covid-19 pandemic with more people working from home. I particularly loved the ‘seated posture support’ as a great way to propriocieve proper posture and give workers a physical reminder not to slouch.

The tips contained in this article are extremely useful to safeguard posture when in front of a computer for a prolonged period. This is the first time that I see a pelvic tilt exercise using a ball. I definitely look forward to try it!

Thank you for this interesting overview on how to get a better ”desk” posture. I had not seen yet the exercise with the coregeous ball where you roll the circumference of the respiratory diaphragm: it is very relaxing. 😀

Thanks for the inspiring article Diane! It’s true that young people usually arent interested in the way they carry themselves, move, or don’t move untill after they are injured. Thanks for the inspiration on the importance of prevention, the ergonomical tips, and how we can better mechanically load our bodies.

Great ideas !

I was already removing by shoes and working barefoot.

I am planing to try the exercices with the Coreagous ball.

These are great tips to easily incorporate into an office setting. I like how accessible and quick the roll outside are and the uses of the coreagous ball. Thank you!

This is a fantastic article. Logically presented, well supported with clear descriptons and video/photo support. I really appreciate the bibliography at the end.

Such an awesome, well thought out, well written article, thank you! I’ll have to do the sternum and diaphragm Coregeous ball roll out, haven’t tried that yet! Thank you for such a great piece. I’ll be re-posting.

These are fantastic! So beneficial for today’s world. Thank you!

This is why I started offering roll out at the office, OfficeRolling. To offer the deskbound a short 20min roll out to increase blood flow, easy pain and loosen up those tissues for better posture and maybe to have more energy after a days work.

Also increase body posture awairness, fell you body in space, so that you correct your sitting and standing posture.

These exercises in the blogg are great thank you, a great addition to the roll out.

This is a fantastic resource that I will be bringing to my colleagues at my 9-5 desk job! Amazing job, Diana, thank you! (And I am in NY as well)!

thank you for your article. This is an epidemic esp for the kids growing up. add the heavy backpacks… along with constant digital time..

Loved the Coregeous ball on the .. Great for an office break when your sleepy

I have regular conversations with my clients about their workday and try to help them identify those patterns and routines that are causing pain and/or anxiety. I then provide them with stretches they can do throughout the day, but I love the examples of how to use the Coregeous® ball! I can’t wait to share these simple suggestions with them!

Super informative article…everyone could benefit from these exercises presented

Thank you for bringing to light this rising epidemic. The public needs to understand how easy it is to be in Sympathetic stimulation. But there are easy ways to mix posture and destress.

This article reminds me of a class I had at the university called Ergonomics, which aims to create a work area appropriate to the type of activity that is performed (office, repetitive movements, standing, etc.), but although I had that class more than 20 years ago, I believe that it is still in diapers, as there are very few companies that care about developing ergonomic work areas and an environment with low stress levels, even though this could save them a lot of money in decreasing hours- man to perform work more efficiently, saving by preventing illness due to physical discomfort due to poor posture and therefore avoiding absences at work. In addition, these problems of poor posture have been increased by the excessive use of technology and stress itself, affecting the metabolism, increasing the risk of musculoskeletal injuries and the well-being of people.

That is why it is important that we try to improve our posture and pause during the day to rest our eyes, at the same time that we can perform some exercises of Yoga Tune Up® and The Roll Model® recommended by Diane.

Mobility in general is the best ergonomics actions to stay well. every one can perfomance ways to do, according to the space and tools can be used. Most manufacturing Jobs in Japan stop people work activities every hour for stretching body for 10 minutes.

This article portrays the importance of our daily habits and how they can impact our well being with a variety of examples. I am really concerned on how our lifestyles are getting more and more into not doing nothing, with technologies that allow you to almost not move and have some things done, our sedentariness is becoming stronger. Being aware of the repercussions is the first step for creating this lifestyle changes. Thank you for showing us the effects of poor posture habits and how can we deal with our posture through massage and breathing awareness.

It was amazing to learn how posture at the desk can really inhibit the breathing mechanics. These are amazing tips and tricks for those who do sit at a desk all day and how they can implement these techniques to save their posture!

Creo este artículo es un aporte maravilloso e imprescindible para las actividades de la vida moderna. Desde edades tempranas, nos vemos obligados a permanecer sentados muchas horas, para estudiar, para trabajar , etc. Nuestros músculos y tejidos se va acortando, van perdiendo elasticidad y las articulaciones trabajan sólo en algunos rangos de movimientos. Los ejercicios propuestos son muy efectivos para contrarrestar o minimizar los efectos de la vida sedentaria. Gracias Diana, voy a ponerlos en práctica !!!

Thank you for helping us to understand how our habits that seem to be harmless are affecting us beyond our postures. And thank you for the tips you give to improve our daily life.

Fantastic article! It’s so crazy to think about how many people are not conditioned or trained to sit correctly or place their body into varied movement to counter more long sedentary moments. To be honest, it never really occurred much to me when I was working a full-time desk job and until I got more involved with yoga and other movement practices (real talk – years in) that I realized how we place our bodies in rather detrimental, unhealthy positions in the long run and train ourselves that this is ok. Your DIY tips are fabulous and a great reminder that we can learn to practice better ergonomics and movement at any point!

Sitting postures on our office chair really affect how our arms, neck, shoulder, back, hip, and even legs feel. I have been having right side shoulder pain for over 20 years even i am only at beginning of my 30s, the overuse of my shoulder by incorrecting writing posture, sitting posture, and carrying heave backpack, i live with pain because these overused muscle and joint, hopefully self care with rolling balls and mindful posture will help to release pain.

I’m a LMT who practices in a corporate environment with a lot of folks who write code for hours on end. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve asked a client, “When you were studying programming, did anyone every teach you how to sit sustainably?” I CAN count how many times they’ve said “yes”: None.

These are terrific movement tools for cultivating self-awareness, remediating imbalance, and encouraging breaks to “check-in” rather than allowing a perpetual “check out.”

Wow this article really hit home for me. I was the person years ago in the first picture with the big X. complete with insomnia, etc, etc. Yoga and Yoga Tune Up helped me become more aware of my body and the effects pore posture has on it. Being opened to the amazing world of YTU therapy balls has really helped undo the past. Now I keep doing those posture checks. Crazy the information you get from your body if you pay attention. Thanks for sharing

Thanks for sharing. I did the ergonomics check-in while sitting down and I was surprised by how poor my posture is while sitting. It is crazy the impact of technology into our physical bodies, all the slouching that is seen everyday. I personally use to be a big couch-potato and once I started moving around more on a daily basis, I started to feel so much better.

So important to keep in mind when you sit at a desk all day like I do. I am guilty of sitting in all kinds of weird positions …. not ergonomically sound at all. I try to at least take movement breaks every once in awhile throughout the day.

Thank you for sharing these tips! I find it interesting that a lot of the things we do and use in daily life requires us to hunch over and crane our head forward vs. having things designed to be lifted up eye and mid-torso level.

I am also concerned about the negative effects of poor posture on young people. The challenge is in convincing them to take the time to change their habits before they are motivated by pain. I really enjoyed this article and the exercises. I will be sharing them with my 16-year old which may not be appreciated as she already calls me the posture police. I will also be sharing them with my yoga students and I know that they will be appreciative. Thank you.

Thank you for the thorough discussion and suggestions to mitigate the effects of sitting through ergonomics. Many of my clients are desk bound for a significant portion of their day. It is always my intent to provide some counter measures for them to take away and use in their work day. I love the pelvic tilts on the Coregeous® Ball, and am looking forward to sharing that along with the other exercises.